Few friendships of the American Revolution were as intense, idealistic, and emotionally resonant as that between Alexander Hamilton and John Laurens. Forged in wartime and sustained through passionate correspondence, their bond was built on shared values, military ambition, and a belief that the Revolution should live up to its bold promises. Their letters reveal not only political thinking, but an emotional intimacy that still surprises modern readers—and helps explain why their friendship features so prominently in Hamilton the musical.

Hamilton and Laurens met in 1777 while serving as aides-de-camp to George Washington. Both were young, brilliant, and impatient with half-measures. In their letters, they wrote about honor, reputation, and the meaning of liberty, often blending political philosophy with personal affection. Hamilton once wrote candidly to Laurens:

“Cold in my professions, warm in my friendships, I wish it were in my power to tell you how much I love you.”¹

While such language was not unheard of among 18th-century gentlemen, the frequency and depth of their correspondence suggest an unusually close bond. Laurens was a confidant—someone Hamilton trusted with his frustrations, ambitions, and moral convictions.

Shared Ideals and Revolutionary Purpose

What truly united Hamilton and Laurens was a shared vision of what the Revolution should achieve. Laurens was among the most outspoken abolitionists of his generation, advocating the enlistment and emancipation of enslaved men in South Carolina. Hamilton strongly supported the idea, writing:

“I wish, my dear Laurens, it might be in my power… to convince Congress to adopt your plan.”²

Their alignment on slavery—radical for the era—reveals how both men believed independence meant more than separation from Britain.

Brothers in Arms

Hamilton and Laurens were also brothers in uniform, bound by danger and ambition. They belonged to Washington’s inner military “family,” alongside figures like the Marquis de Lafayette. They wrote often about glory, risk, and the frustrations of staff duty. Hamilton once worried that Laurens was “too fond of glory,” a concern that reflected his own willingness to court danger.³

Loss and Legacy

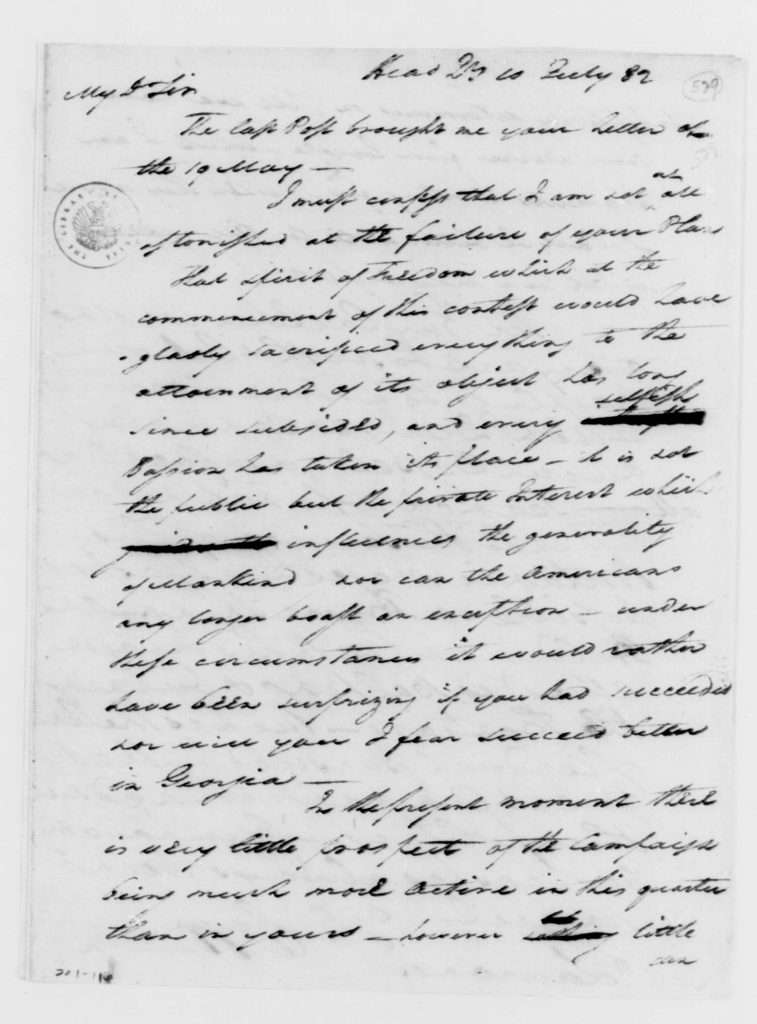

Laurens’ death in 1782—killed in a minor skirmish after the war was effectively over—devastated Hamilton. Writing to General Nathanael Greene, Hamilton mourned:

“Poor Laurens! He has fallen in a paltry skirmish… The world will feel the loss of a man who has left few equals behind him.”⁴

The grief was lasting. Laurens’ death came just as the ideals he fought for seemed within reach, leaving Hamilton—and the new nation—to carry on without him.

Hamilton the musical captures the energy of this friendship—its urgency, idealism, and tragedy—even if it compresses the history. In life, Hamilton and Laurens believed the Revolution could remake the world. In death, Laurens became one of the sacrifices that made that vision possible.

On the Hamilton & Washington in New York walking tour, their friendship is explored as a window into a younger, more radical generation within Washington’s army—men who debated liberty late into the night, challenged each other’s assumptions, and imagined an America that did not yet exist. Standing in the very places where Hamilton later shaped the nation, visitors are invited to consider how much of his vision was forged not only in battle, but in friendship.

- Alexander Hamilton to John Laurens, April 28, 1778, Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-01-02-0064.

- Alexander Hamilton to John Laurens, March 14, 1779, Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-02-02-0245.

- Alexander Hamilton to John Laurens, June 1779, Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-02-02-0270.

- (Note: Some June 1779 letters are undated or partially dated; this citation reflects standard archival usage.)

- Alexander Hamilton to Nathanael Greene, January 26, 1783, Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-03-02-0204.