In March 1783, as the Revolutionary War drew to a close, George Washington drafted a letter from Newburgh, New York to his trusted associate Alexander Hamilton that revealed the depth of his vision for the newly independent United States. This letter reflects not only Washington’s happiness at the close of the war but also his concerns and vision for the future of the United States.

Unity

Washington’s letter reveals his optimism about the potential of the new nation to become “a great, respectable, and happy People” but also his awareness that realizing this vision would require more than just the end of the long conflict with England. Internal divisions, petty politics, and “unreasonable jealousies & prejudices,” he understood, could undermine the nation’s progress, making it vulnerable to foreign powers seeking to dissolve the government running under the Articles of Confederation through intervention.

Washington’s words serve as a powerful reminder of the importance of unity and cooperation in achieving greatness. He understood that the path to success was about building a strong, cohesive society where all citizens could thrive.

Reform

One of the most striking aspects of Washington’s letter is his prescience in his candid assessment of the defects in the existing Confederation and the need for reform and and a nation built upon “liberal & permanent principles.” He understood that many of the war’s challenges, including its prolongation and expense, were due to the lack of power vested in Congress. This insight highlights Washington’s foresight in recognizing the need for a more robust central government, a vision that he and Alexander Hamilton shared that would later shape the creation of the U.S. Constitution.

Washington’s call for reform was not simply intellectual; it was deeply personal. He had experienced firsthand the difficulties caused by a weak Congress during the war. The letter reveals his frustration with the “prejudices of some” and the “designs of others,” which made it challenging to implement needed reforms

Collaboration

What makes Washington’s letter truly remarkable is his willingness to collaborate and seek advice. He eagerly awaited Hamilton’s thoughts on these matters, demonstrating the value he placed on other perspectives. This approach to governance is still essential today, as leaders must navigate complex challenges and, for the betterment of the nation, engage with different viewpoints.

Lessons

Washington’s letter offers wisdom that resonates deeply in today’s divisive political landscape. His emphasis on unity, principled governance, and visionary leadership is a powerful reminder of how to build a strong and prosperous nation.

In an era marked by polarization, Washington’s words remind us of the importance of putting aside our differences and working towards common national goals. His call for a robust and effective government structure is a reminder that systemic issues must be addressed to ensure the well-being of all citizens.

Conclusion

George Washington’s letter to Alexander Hamilton is a blueprint for building a better future. It reminds us that the strength of a nation lies in its ability to unite, reform, and lead with vision and integrity. As we navigate the complexities of today, Washington’s letter stands as a testament to the enduring power of unity, collaboration, and principled leadership.

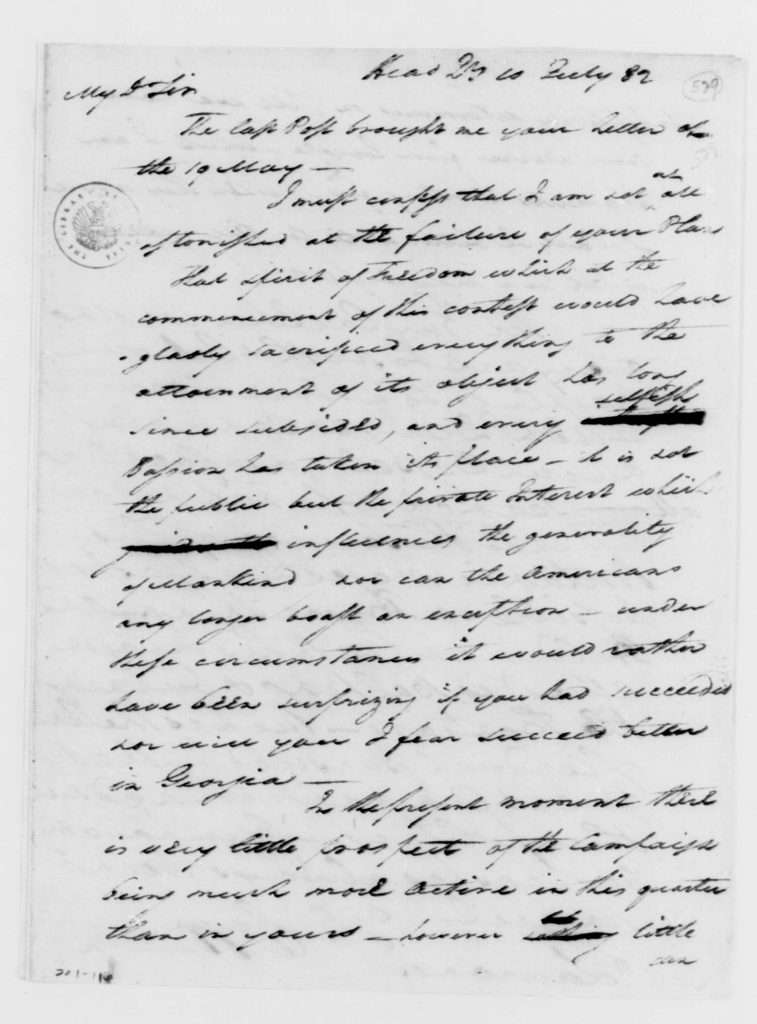

Here is the complete letter:

From George Washington to Alexander Hamilton, 31 March 1783

Newburgh 31st March 1783

Dear Sir,

I have duly received your favors of the 17th & 24 Ulto—I rejoice most exceedingly that there is an end to our Warfare, and that such a field is opening to our view as will, with wisdom to direct the cultivation of it, make us a great, a respectable, and happy People; but it must be improved by other means than state politics, and unreasonable jealousies & prejudices; or (it requires not the second sight to see that) we shall be instruments in the hands of our Enemies, & those European powers who May be jealous of our greatness, in Union to dissolve the confederation—but to attain this, altho’ the way seems extremely plain, is not so easy.

My wish to see the Union of these States established upon liberal & permanent principles—& inclination to contribute my mite in pointing out the defects of the present Constitution, are equally great—All my private letters have teemed with these Sentiments, & whenever this topic has been the Subject of conversation, I have endeavoured to diffuse &enforce them; but how far any further essay, by me, might be productive of the wished for end–or– appear to arrogate more than belongs to me, depends so much upon popular opinions & the temper and disposition of People, that it is not easy to decide. I shall be obliged to you however for the thoughts which you have promised me on this Subject, and as soon as you can make it convenient.

No Man in the United States is, or can be more deeply impressed with the necessity of a reform in our present Confederation than myself—No Man perhaps has felt the bad efects of it more sensibly; for to the defects thereof, & want of Powers in Congress may justly be ascribed the prolongation of the War, & consequently the Expences occasioned by it. More than half the perplexities I have experienced in the course of My command, and almost the whole of the difficulties & distress of, the Army, have there origin here; but still, the prejudices of some—the designs of others—and the mere Machinery of the Majority, makes address & management necessary to give weight to opinions which are to Combat the doctrines of these diferent classes of Men, in the field of Politics.

I would have been more full on this subject but the bearer (in the Clothing department) is waiting—I wish you may understand what I have written. I am Dr Sir Yr Most Obed Servt

Go: Washington

P.S. The inclosed extract of a Letter to Mr Livingston, I give you in confidence—I submit it to your consideration, fully perswaded that you do not want inclination to gratify the Marquis’s wishes as far as is consistent with our National honor. (1)

1 George Washington to Alexander Hamilton, 31 March 1783, Founders Online, National Archives, accessed March 27, 2025, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-10968.

Find the Washington & Hamilton in New York tour and other New York Historical Tours at Revolutionary Tours NYC