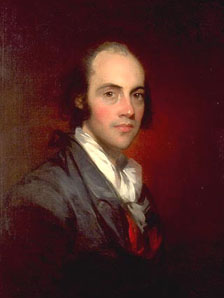

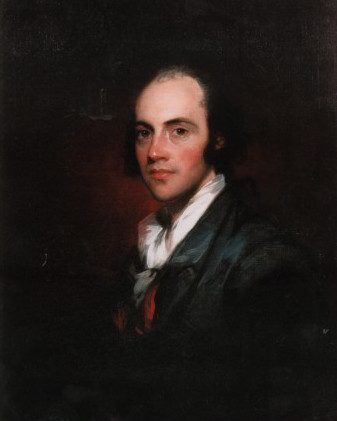

The duel between Aaron Burr and Alexander Hamilton on July 11, 1804 was one of the most infamous events in American history, rooted in fierce political rivalry and personal animosity. Their conflict erupted after a contentious New York gubernatorial race, where Burr, then Vice President, lost to Morgan Lewis, partly due to Hamilton’s vocal opposition to his candidacy. The final catalyst for the duel came when a letter from Dr. Charles D. Cooper, published in the Albany Register, accused Hamilton of describing Burr as an untrustworthy “dangerous man,” and of having expressed “a still more despicable opinion” of Burr.

The Cooper Letter in the Albany Register

Dr. Cooper’s letter read:

“I assert that Gen. Hamilton and Judge Kent have declared, in substance, that they looked upon Mr. Burr to be a dangerous man, and one who ought not to be trusted with the reins of government.” (1)

Cooper further reported Hamilton’s supposed utterance of an even worse “despicable” opinion, which triggered Burr to confront Hamilton directly. This public airing of private resentments created a scandal Burr felt demanded satisfaction.

Burr’s Letters to Hamilton

Upon seeing Cooper’s published remarks, Burr sent his first challenge letter to Hamilton on June 18, 1804:

“You must perceive, sir, the necessity of a prompt and unqualified acknowledgement or denial of the use of any expression that would warrant the assertions of Dr. Cooper.” (2)

Burr demanded Hamilton either confirm or deny he made the statements attributed to him. Hamilton’s reply was evasive, refusing a categorical answer, which inflamed the conflict. Burr followed up with another letter dated June 22:

“I relied with unsuspecting faith that from the frankness of a Soldier and the Candor of a gentleman I might expect an ingenuous declaration; that if, as I had reason to believe, you had used expressions derogatory to my honor, you would have had the Spirit to Maintain or the Magnanimity to retract them…” (3)

Burr made clear that only an explicit apology or retraction would suffice, expressing disappointment at what he saw as Hamilton’s equivocation.

Hamilton’s Responses

Hamilton’s replies were measured but firm. In his June 20, 1804 letter, Hamilton rebuffed Burr’s demand:

“I have become convinced, that I could not, without manifest impropriety, make the avowal or disavowal which you seem to think necessary.” (4)

Hamilton further explained that his statements about Burr were general political criticisms and not a direct attack on Burr’s honor. He conceded to “abide by the consequences,” implicitly accepting the possibility of a duel. Throughout these exchanges, Hamilton maintained a tone of civility and principle, while trying to avoid a public retraction and escalation, but Burr saw this as evasion.

The Path to the Duel

The repeated written refusals to apologize and escalating tone brought both men to an impasse. Burr closed his final letter:

“Thus, sir, you have invited the course I am about to pursue, and now your silence impose it upon me.” (5)

Hamilton, meanwhile, prepared drafts in case he would not survive, expressing his moral aversion to dueling but accepting the practical realities of honor and reputation in that era.

These exchanges show how the collision of politics and pride produced one of America’s defining moments, ending in Hamilton’s early demise and reshaping the early republic’s view of honor and violence.

The unfortunate conclusion of the Burr–Hamilton duel reveals a profound complexity at the heart of their relationship, shaped by fifteen years of political rivalry, deep-seated mistrust, and competing ambitions for influence in the new nation. Though both men had worked together in law and served in the American Revolution, their differences became irreconcilable as Burr’s flexible political allegiances repeatedly clashed with Hamilton’s principled Federalism, leading Hamilton to view Burr as an obstacle to the country’s future. Hamilton’s letter before the duel admitted no personal hatred, but emphasized his duty to oppose Burr for the greater good.

For both Hamilton and Burr, the concept of honor was not merely personal character, but a public currency essential for survival in the Early Republic. Burr’s demand for a full retraction was rooted in the era’s sometimes unforgiving standards, where reputation dictated power; refusing the challenge would have meant public humiliation and hence political death for either man. Hamilton, meanwhile, struggled with the moral consequences of dueling but understood that conceding would compromise his usefulness and legacy as a leader. Ultimately, their ideas of honor forced them onto the dueling ground—not out of animosity alone, but from a belief that only through defending reputation could they uphold their dominance, even at ultimate personal cost. The heartbreak was not just in the loss of Hamilton’s life, but in the way their fixation on personal honor transformed a private quarrel into a moment that transformed early American political culture.

Explore Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr in the Hamilton & Washington in New York walking tour, offered as both a public and private tour. Book the tour today!

Sources: