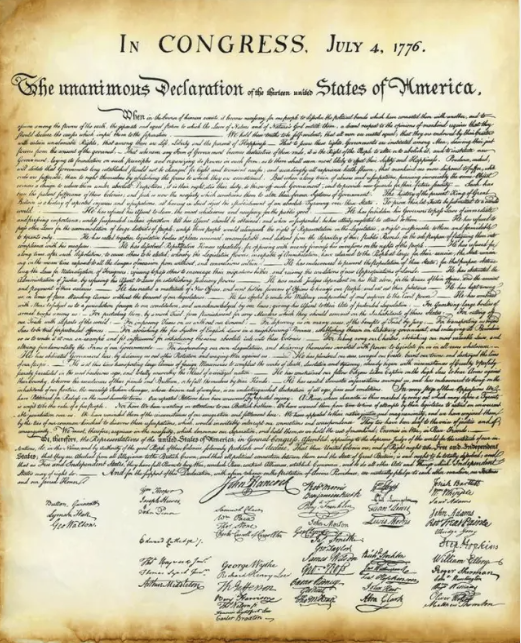

Every July, Americans celebrate the “unanimous” Declaration of Independence adopted on July 4, 1776. But there’s a fascinating wrinkle hiding behind that famous word: on July 4, the vote wasn’t actually unanimous. New York — a critical colony and future major battleground of the Revolution — had not authorized its delegates to support independence. So why does the document proudly proclaim “the unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America”? The answer reveals the messy, human reality behind one of the nation’s most important moments.

To understand this, we need to step back a couple of days before July 4. On July 2, 1776, the Continental Congress voted on Richard Henry Lee’s resolution declaring the colonies independent from Great Britain. Twelve colonies voted in favor. New York abstained — not because its delegates were loyal to the Crown, but because they were bound by instructions from their Provincial Congress, which had not yet authorized a vote for independence. In an era when delegates followed strict legal instructions from their home governments, they simply could not say yes on their own authority.

Two days later, on July 4, Congress approved the final wording of the Declaration of Independence. New York again refrained from voting. Yet importantly, the colony did not oppose the Declaration either. The delegates understood the direction events were moving — they were simply waiting for official approval from home.

That approval arrived on July 9, 1776, when New York’s Provincial Congress met in White Plains and finally endorsed independence. With that decision, New York’s delegates were free to join their colleagues. In the weeks that followed, as the Declaration was printed, circulated, and eventually engrossed for signing in August, all thirteen states had formally aligned themselves with the revolutionary cause. By the time most delegates signed the famous parchment on August 2, the colonies truly were united — making the description “unanimous” politically accurate, even if it wasn’t technically true on July 4 itself.

New York’s hesitation reflects the colony’s unique position in 1776. Economically tied to Britain, politically divided, and strategically vulnerable, New York faced enormous risks. British forces were already preparing to target the city, and many residents were cautious about a complete break with the empire. Understanding this context adds depth to the story of independence and reminds us that unity was achieved through a process — not a single dramatic moment.

This nuance is just one example of how Revolutionary-era history is often more complex and compelling than what we learned in school. On Revolutionary Tours NYC’s Hamilton & Washington walking tour, visitors explore the real-life settings where New York wrestled with loyalty, resistance, and ultimately revolution. From Federal Hall to Fraunces Tavern and beyond, the tour reveals how figures like Alexander Hamilton and George Washington navigated the uncertain days when independence was far from guaranteed.

So the next time you read the Declaration’s opening line, remember that “unanimous” reflects the final unity the colonies achieved — not the perfectly synchronized vote we often imagine. The road to independence was uneven, cautious, and deeply human — and New York’s late but decisive support is a powerful reminder that the Revolution was built step by step, colony by colony, until a shared vision finally emerged.

👉 Sign up today for the Hamilton & Washington Walking Tour and experience the American Revolution where it happened.