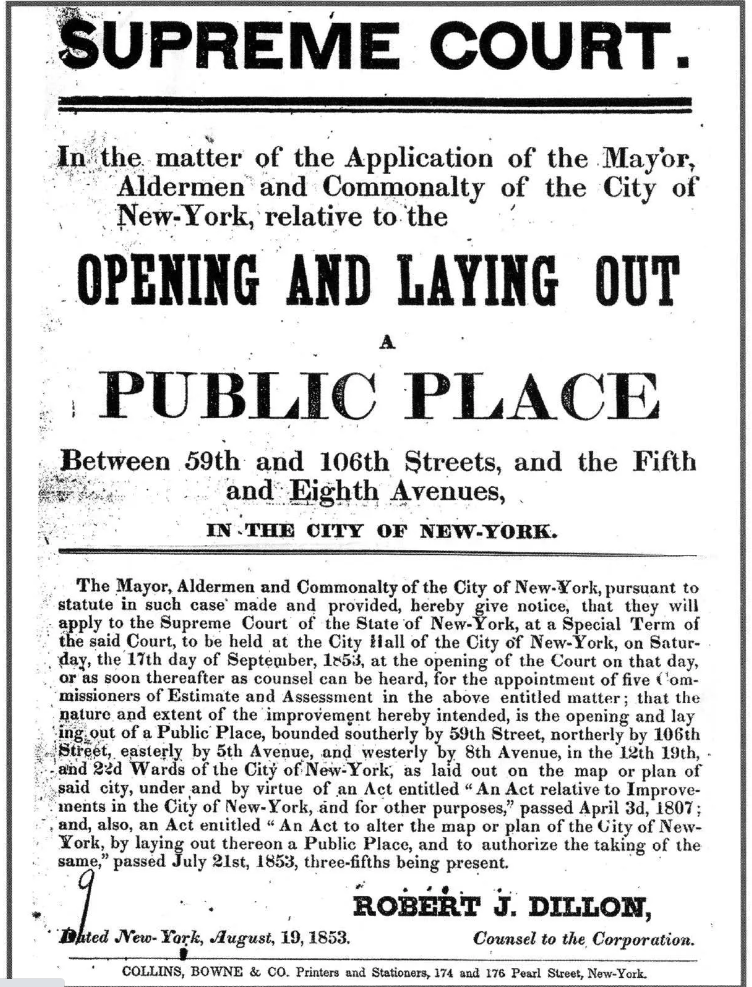

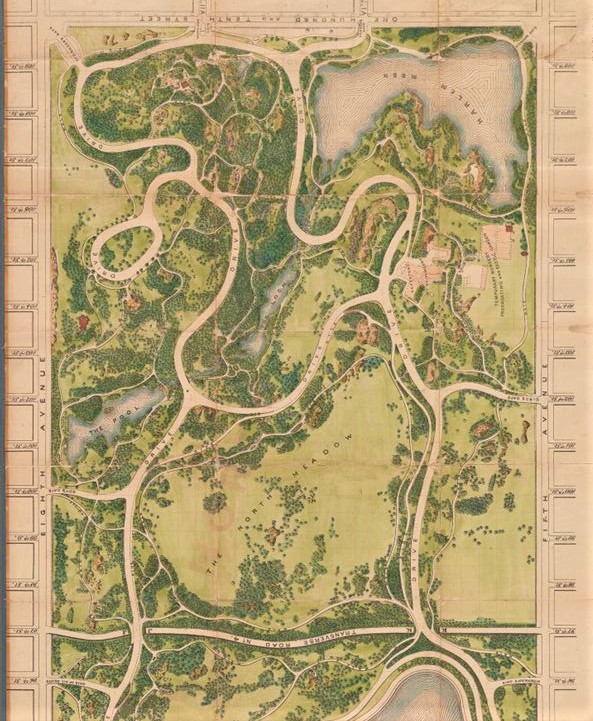

In the heart of what is now the Central Park landscape once stood Seneca Village, a vibrant and empowered African American and immigrant community that existed on the land between 1825, two years before the end of slavery in New York State, and 1857. The community was between 82nd and 89th Streets and between Seventh and Eighth Avenues. Seneca Village was established when white property owners John and Elizabeth Whitehead, uptown landowners, subdivided their property and sold off 200 lots. The first buyer was Andrew Williams, a 25-year-old African American bootblack (shoe shiner) who purchased three lots for $125. Williams was soon joined by others seeking opportunity and refuge from the crowded, disease-ridden, and discriminatory conditions of Lower Manhattan. Epiphany Davis, a store clerk, bought 12 lots for $578, and the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church acquired six more. By the mid-1850s, it had grown to around 50 homes, three churches, a school for African-American children, and burial grounds. White European immigrants began moving to Seneca Village in the 1840s.

Seneca Village was remarkable not just for its growth but for its diversity and autonomy. At its peak, the community numbered about 225 residents, two-thirds of whom were Black, with the rest being Irish and possibly German immigrants. More than half of the Black residents were property owners, a rare achievement since, at the time, only 10% of the city’s entire population owned land. This land ownership also conferred the right to vote for Black men (a $250 property-ownership requirement and three years’ residency in the state began in 1821), as well as stability and self-determination.

Andrew Williams, the village’s first landowner, lived there with his wife, Elizabeth, and their family from 1825 until 1857, when the city acquired the land through eminent domain to create Central Park. Williams’s story is emblematic of the community: he built a home, raised a family, and participated in a thriving middle-class neighborhood that included churches, schools, and gardens. Epiphany Davis, another prominent resident, invested in multiple lots and helped anchor the village’s economic and social fabric.

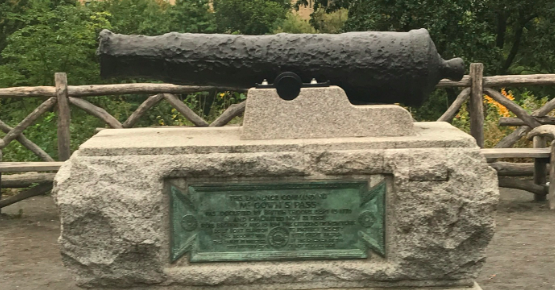

The landscape of Seneca Village was varied, featuring rolling hills, rocky outcrops, and meadows. Residents cultivated gardens, raised livestock, and drew water from a natural water source that became known as Tanner’s Spring, while orchards and barns dotted the landscape.

Seneca Village offered a rare sanctuary of Black property ownership and community in antebellum New York. Its erasure in 1857 for Central Park’s creation was a profound loss, but ongoing research, archaeological work, and public commemoration since it’s rediscovery in 1992—by historians Roy Rosenzweig and Elizabeth Blackmar—are restoring its rightful place in the city’s history—a testament to resilience, aspiration, resourcefulness, and community in the face of adversity. Find more about Seneca Village on the Secret Places of Central Park and Central Park Experience walking tours, as well as a private tour focusing on Seneca Village offered for groups of adults, students, and corporate employees.